Snapvocacy: Stories from the Front Lines

-

Week 8: Resiliency Part II

For the final week of our National Campaign entitled ‘Snapvocacy’, we thought we would personally ask refugees what resiliency means to them. The answers below are given from refugees from Iraq who have been in Canada for almost 3 years. (Note: Parental consent was received to post this picture.)

What does ‘resiliency’ mean to you?The Mother

To me it means to be adaptable, and also to be able to communicate with others. It also means that I am dependent on my own self and not on others.

How do refugees and migrants demonstrate resilience?The Mother

I think I try to be involved in my community and for example find a job here in Canada. Also, in order to make my integration easier I try hard to improve my English. I really enjoy trying the new food; it tastes good and fresh!

Daughter, 10 years old

In Iraq, there are almost no rules. Here in Canada, I do my best to listen to the rules in class and be respectful to the teachers. I like learning English, and even a little bit of French. Also, it is important to adapt to the security rules. For example, in Iraq we do not wear a helmet when we ride a bicycle, but here it is mandatory.

What factors challenge the resiliency of refugees and migrants that are newcomers to Canada (e.g. prejudice, racism etc.)?

The Mother

Although we feel that the others in Canada are inclusive regardless of our culture and are respectful, I find it really hard as a mother to make new relationships. It can be really hard to find people that have the same culture as me and sometimes I feel quite isolated. I am far away from my family, relatives and friends. Thankfully the activities my kids do help me to get to know others parents.

Another thing I find difficult is for my skills to be recognized. My working certificate it not valid here and it feel like I have to start from zero.

Educational Links

To highlight resiliency, we wanted to showcase stories from individuals across the world. Please see the links below for videos of personal testimonies.

The Harrowing Personal Stories of Syrian Refugees, in Their Own Words- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6b5H7je4m1A/

Refugee stories: Life-threatening sea journeys, UNHCR- https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/stories.html

Italy: Haunted by a Sinking Ship, UNHCR- https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/stories.htmlhaunted-sinking-ship-italy-p60028.html

Refugee 613- https://www.refugee613.ca/

Connecting Ottawa- http://connectingottawa.com/

Coalition of Community Health and Resource Centres of Ottawa- http://www.coalitionottawa.ca/

Ottawa Newcomer Health Centre- https://onhc.ca/

Walk In Counselling Clinic- http://walkincounselling.com/

Counselling Programs at Jewish Family Services (JFS)- http://www.jfsottawa.com/counselling-programs/

-

Week 8: Resiliency Part I

Humans of Advocacy Campaign – Resilience

An interview with Zewditu Wayeissa, Settlement Counsellor, Resettlement Assistance Program (RAP), Saskatoon Open Door Society. Zewditu is originally from Ethiopia and has been in Canada since 1997. She began working with the Saskatoon Open Door Society in 2004.

What does resiliency mean to you and the refugee population that you serve?

Resiliency is all about strength and hope. The majority of people I work with, especially the refugees, are hopeful for life. They always hope for a better life. They are resilient, hoping for peace. They have crossed so many roads, and come so many miles just to find safety and a better life for their loved ones that even when something goes wrong they just hope for the best and keep pushing forward. That is resiliency. They hope to create a safe place for their children and live in a peaceful nation and country.

In the context of healthcare access, what barriers have you or your clients found both when they first arrive to Canada and in later years?

The first barrier is language. Without enough English, people can’t express what they need or what their concerns are. They can’t express how they feel and they can’t understand what the doctor or nurse is telling them.

Another barrier is lack of knowledge. Often refugees do not understand what healthcare services available. They don’t know when to go to Emergency, or to a walk-in clinic, or to call their doctor. They think that health care services here will be the same as they were back home. Transportation can also be a barrier, especially when someone is sick and they have to learn to take the bus.

Of course culture can also be a barrier, especially for females who don’t want to see a male doctor. So then we have find a female and the wait time may be longer. It can be very stressful for the client. People also don’t have their family here with them. It’s a reality, but there is a lot of help everywhere and there are many people willing to help the client find their way no matter what they need.

Can you share a story of a particularly resilient individual or family you have encountered in your work (while maintaining privacy and confidentiality)?

I have worked with many resilient people but one that comes to mind right away is a family of four from Africa. When they arrived in 2017, their 8 year old son had multiple health problems. He had just had surgery in Kenya but would need further treatment—and surgery. He was very sick. The wife was also sick when she arrived but didn’t know what the problem was because she couldn’t afford medical care back home. She accepted this because she was used to living in a class system without the status or the money to afford health care. When they arrived in Saskatoon, she was diagnosed with cancer. She began receiving chemotherapy. She was very scared and felt she was going to die. She was sad because she would be leaving behind her husband and their two children. But, the doctor told her that in Canada there is no class and people are treated the same. He told her that even if Michelle Obama was here and was sick she would receive the same care. That was such meaningful and special news to hear. She had always felt very sad but when she heard the doctor’s words, she smiled for the first time in a long time. Now, her resiliency comes from knowledge, faith and hope and not just accepting the worst. Everyone is doing whatever they can for her and her son and her family and they are doing better.

Are there other resources, in addition to the Saskatoon Open Door Society, that healthcare providers should be knowledgeable about so they may recommend them to their refugee patients? (Local, provincial or national programs)

It is very important for people to have a connection to their cultural community, a place of worship and settlement agencies. Healthcare providers should familiarize themselves with what services are in the community. Online translation services are also important.

Another resource is REACH, Refugee Engagement and Community Health and it is hosted by the Saskatoon Community Clinic. REACH is for refugees who need initial health assessments and follow up services. Clinics are held at the Community Clinic’s downtown location each Wednesday morning and services include Diagnostic (lab, x-ray, ECG) and Pharmacy. An interpreter will accompany the client for the first visit and after that, interpretation is available via telephone. University of Saskatchewan College of Medicine physicians provide medical care. Appointments for these clinics are arranged through the Global Gathering Place, a Saskatoon settlement agency, in collaboration with the Saskatoon Open Door Society. The Community Clinic provides limited appointments with a Nurse Practitioner for follow up care and access to Diagnostic and Pharmacy Services. The client may also be seen by a healthcare provider in the community.

REACH is a partnership with the Saskatoon Community Clinic, University of Saskatchewan College of Medicine (Family Medicine, Paediatrics, Community Health and Epidemiology), Global Gathering Place, Saskatoon Open Door Society, Saskatoon Health Region (Population and Public Health; Primary Health; Mental Health and Addictions) and TB Prevention and Control Saskatchewan.

-

Week 6: Local/Community Organizations

How does your group facilitate refugee settlement in Ottawa?

Immigrant Women Services Ottawa is a non-profit, community-based social service agency providing the highest quality of culturally-appropriate services to newcomer women and their children. Established in 1988, the organization provides settlement counselling, crisis intervention, advocacy, language interpretation, support groups, language classes and employment workshops.

The organization creates opportunities for newcomer women as they integrate and settle into a new society and achieve their personal goals. Every year, over 2,000 women and their children are helped by IWSO’s dedicated staff and volunteers.

In your opinion, what are the main challenges refugees and migrants face when settling in Canada?

The main challenges that we see our clients facing are health (physical as well as mental wellbeing), housing, and isolation.

In your opinion, what are the main priorities that refugees and migrants have when arriving and settling in Canada?

The main priorities that we see our clients focused on are finding employment and finding housing.

-Immigrant Women Services Ottawa

Educational Links

Services for Refugee Claimants in the Ottawa Area

Please see the following link from Connecting Ottawa and Refugee 613 for a quick information guide for a refugee claimant in Ottawa:

http://connectingottawa.com/sites/all/files/Refugee%20Claimant%20Resource%20for%20Ottawa_0.pdf

Please see the following link for stories of people in the Ottawa area who helped welcome Syrian refugees in 2016 (Source: Refugee 613): http://ottawarefugeestory.ca/

Organizations and Health clinic in the Ottawa Area

Catholic Centre for Immigrants- http://cciottawa.ca/

Immigrant Women Services Ottawa- http://www.immigrantwomenservices.com/

Ottawa Community Immigrant Services Organization- https://ociso.org/

Refugee 613- https://www.refugee613.ca/

Connecting Ottawa- http://connectingottawa.com/

Coalition of Community Health and Resource Centres of Ottawa- http://www.coalitionottawa.ca/

Ottawa Newcomer Health Centre- https://onhc.ca/

Walk In Counselling Clinic- http://walkincounselling.com/

Counselling Programs at Jewish Family Services (JFS)- http://www.jfsottawa.com/counselling-programs/

-

Week 5: Long-term Care & Sustainability

A conversation with Neena Lamba, Settlement Coordinator at the Thunder Bay Multicultural Association

In what capacity do you work to support refugees and migrants in the region of Thunder Bay?

“The Thunder Bay Multicultural Association (TBMA) assists immigrants, refugees, refugee claimants and people who have temporary status in Canada (visitors, students, workers with short term work permits).

The TBMA offers a one-stop shop for community information and settlement services. Settlement workers provide newcomers with practical assistance for the challenges of everyday life in Canada. This year we served 663 new clients within their first year of arrival to Canada. These individuals were from 50 countries including Aruba, Bahamas, Bangladesh, Burma, China, Colombia, Democratic Republic of Congo, Cuba, Egypt, Ethiopia, England, Eritrea, France, Germany, Great Britain, Guatemala, Hungary, India, Iran, Iraq, Italy, Jamaica, Kazakhstan, Mexico, Morocco, Myanmar, Namibia, Nepal, Nigeria, New Zealand, Pakistan, Palestine, Philippines, Poland, Portugal, Russia, Servia, Sierra Leon, Sudan, South Korea, Uganda, Syria, Senegal, Turkey, Thailand, Taiwan, Trinidad & Tobago, Vietnam, Zimbabwe, and the USA.

The immigration categories were Family Class (immigrants who are sponsored by a Canadian citizen or permanent resident who is a family member), Economic Immigrants (selected on their ability to contribute to Canada’s economy/labor market), Refugee Classes, and others (if the client has a particular circumstance that would preclude the client from the other existing categories).

According to our records, 80% of the newcomers are primary migrants and 20% are secondary migrants. A primary migrant is someone who has come directly to Thunder Bay District and neighboring cities in North West Ontario. Secondary migrants have initially immigrated to a different city in Canada, and relocated to the Thunder Bay and Northwest region.

Settlement workers at the TBMA are heavily involved in helping immigrants and refugees achieving a sustainable settlement by taking the initiative to reach out to newcomer individuals and families, conduct a Needs Assessment to assist families to prioritize settlement needs and provide them with settlement information, orientation, and referrals to agencies and community resources and services when there are barriers due to language and/or culture. The TBMA assists the individuals and families in their transition by acting as an advocate on the newcomer’s behalf when appropriate, providing comprehensive employment counselling, delivering a variety of workshop and integrating them in community services and activities.”

What are the issues surrounding sustainable settlement and long-term refugee health and wellbeing?

“Some of the issues that we have encountered include: language barriers and the need for interpretation, difficulty in accessing primary care in clients with multiple complex chronic health issues, lack of appropriate dental care, and other detrimental health habits such as high rates of smoking and poor nutrition stemming from more complex health determinants.

In our experience, the greatest barrier for all the refugees in a sustainable settlement is language. The clients don’t understand English or French or don’t speak them proficiently, so most require interpreters, especially for complicated health care issues and appointments. Unfortunately, with the great variety of language needs, resources can be scarce for some refugees. Another big hurdle is the paperwork required under the Interim Federal Health plan that many newcomers have as their only health insurance.”

What can we do in working with refugees and migrants to help them achieve a sustainable settlement and long-term health and well-being?

First steps in assisting refugees and migrants achieve this goal could begin at the community level with initiatives such as:

- Workshops for health and well-being, i.e. language/culture inclusive smoking cessation programs

- Better interpretation service in hospital, especially at the ER

- Respecting spiritual aspects of end-of-life care for Muslim patients

- Simplified paperwork that is more amenable to translation and interpretation, especially in an emergent situation.

- Good knowledge of and referrals to various free programs of TBMA and other Settlement Services around housing, employment, language, education, health, etc.

What makes you passionate about your work?

We all at TBMA are very passionate to assist newcomers to Canada as most of the frontline workers are immigrants themselves and understand the process and barriers. They have some idea about the needs of newcomers plus what kind of challenges they face when they come to a new country and what will be their immediate settlement needs.

One of our settlement workers is an International Medical Graduate and he is working on his credential accreditation. He speaks Arabic and accompanies many clients to their medical appointments. He says “I liked to help the refugees as most of them came from the same culture and language as me and having a medical background, I was able to help them as it is sometimes hard to translate medical terms from English to other languages.”

Suggested resources:

http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p3VD.pl?Function=getVD&TVD=323293&CVD=323294&CLV=0&MLV=4&D=1

http://www.thunderbay.org/programs-services/youth-settlement-program/

https://www.movetonwontario.ca/en/live/living-in-northwestern-ontario.aspx?_mid_=161

https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/refugees/canada-role.html

https://www.thunderbay.ca/en/recreation/apply.aspx

http://www.thunderbay.ca/

https://www.mcss.gov.on.ca/en/mcss/programs/social/ow/apply.aspx

https://www.cleo.on.ca/en

https://www.legalaid.on.ca/en/info/interpreter_services.asp

https://www.cleo.on.ca/en

https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/refugees/canada-role.html

http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/

Local health related agencies who have been extra helpful to our refugee and newcomer clients are:

- Thunder Bay District Health Unit (TBDHU)

- NorWest Community Health Centre

- TBRHSC

- Harborview Optometry

- Scott Family Dental

- Thunder Bay Diabetes Centre

- Maternity Care Midwives of Villa St

- Healthy Smiles Ontario program of TBDHU for young refugee children

- Thunder Bay Social Services Administration (TBDSSAB)

- Northwest Employment Works (NEW)

- Port Arthur Clinic

- Nurse Practitioner from Norwest Community Health Centre

- Community Care Access Centre (CCAC)

- Lutheran Community Health Centre

- Thunder Bay Counselling Centre

- Natural Smiles Dental Clinic

- St Joseph Health Care Centre

- Catholic Family Development Centre

- Norther Medical Grants for sick children

- Rainbow Health Ontario

- Limerick Walk in Clinic

- Hearing Society at Golf Clinic

- George Geoffrey Children Centre

- Ridgeway Clinic

- Fort William Clinic

- Walser Physiotherapy

- Victoria Ville Physiotherapy Centre

Compiled by

Neena Lamba

Settlement Coordinator of TBMA

-

Week 4: Language

An interview with Mandi Irwin

Mandi Irwin is a family physician at the Nova Scotia Health Authority's Newcomer Health Clinic, in Halifax, NS. She graduated from Dalhousie University in 2008 and completed her Family Medicine training in 2011. She has practiced Family Medicine throughout Nova Scotia in both urban and rural settings. Her medical interests include marginalized or vulnerable populations and refugee medicine. She has a teaching appointment from Dalhousie University and started teaching students and residents in 2012.

How did you become involved in refugee/migrant health/the Newcomer Clinic?

In 2012 the federal government under Stephen Harper cut IFHP (Interim Federal Health Program) funding essentially eliminating access to vision, dental, drug and other essential health benefits for refugee claimants. Refugee claimants were having trouble access physicians and hospitals, even in emergency situations. A group of 4 concerned physicians in Halifax (myself, Leisha Hawker, Tim Bood and Tim Holland) were upset about this lack of access and potential harms so we collaborated with ISANS (Immigrant Settlement Association of NS) and the Halifax Refugee Clinic (a legal clinic for refugees) to start a health clinic that would address not only the needs of refugee claimants but also all newcomers. Over the years our clinic has grown and now has almost 2000 patients. We have 2 full-time doctors, many part-time doctors, a nurse practitioner, and a family practice nurse.

My own personal interest in newcomer health stems from my experiences prior to medical school. My 1st degree was in International Development Studies. And I have always been interested in health of at risk populations.

In your work with the Newcomer Clinic, how do you support language and culture?

We use interpreters, in person, on the phone and through a video link. We encourage our patients to use whatever form of interpretation feels best for them. We also encourage them to try appointments in English once they consider themselves ready. Culture can be more challenging for any outsider. But such a great opportunity to learn! I ask whenever I don’t know how to act/what to consider. I believe that a culturally sensitive physician wants to create a safe space for any patient and acknowledges that one way to do that is to keep an open, non-judgmental mind and ask plenty of questions. I try to stay away from broad overarching statements or beliefs about any cultural group. But I also try to educate myself about things such as Ramadan; all the while remembering that one person’s practice of Ramadan may look different from another’s. So I ask.

Any advice for medical students on getting involved with this important work?

Be open, non-judgmental and humble (but I would say that about ANY medicine you practice). Don’t be worried about potential communication challenges; they exist in all clinical encounters even between people who are culturally similar. Have fun!

Links

Newcomer Health Clinic

http://www.nshealth.ca/content/newcomer-health-clinic

https://www.yourdoctors.ca/blog/health-care/doctors-making-a-difference-refugee-health

Immigrant Services Association of Nova Scotia

http://www.isans.ca/

Halifax Refugee Clinic

http://halifaxrefugeeclinic.org/

-

Week 3: Common Health Problems

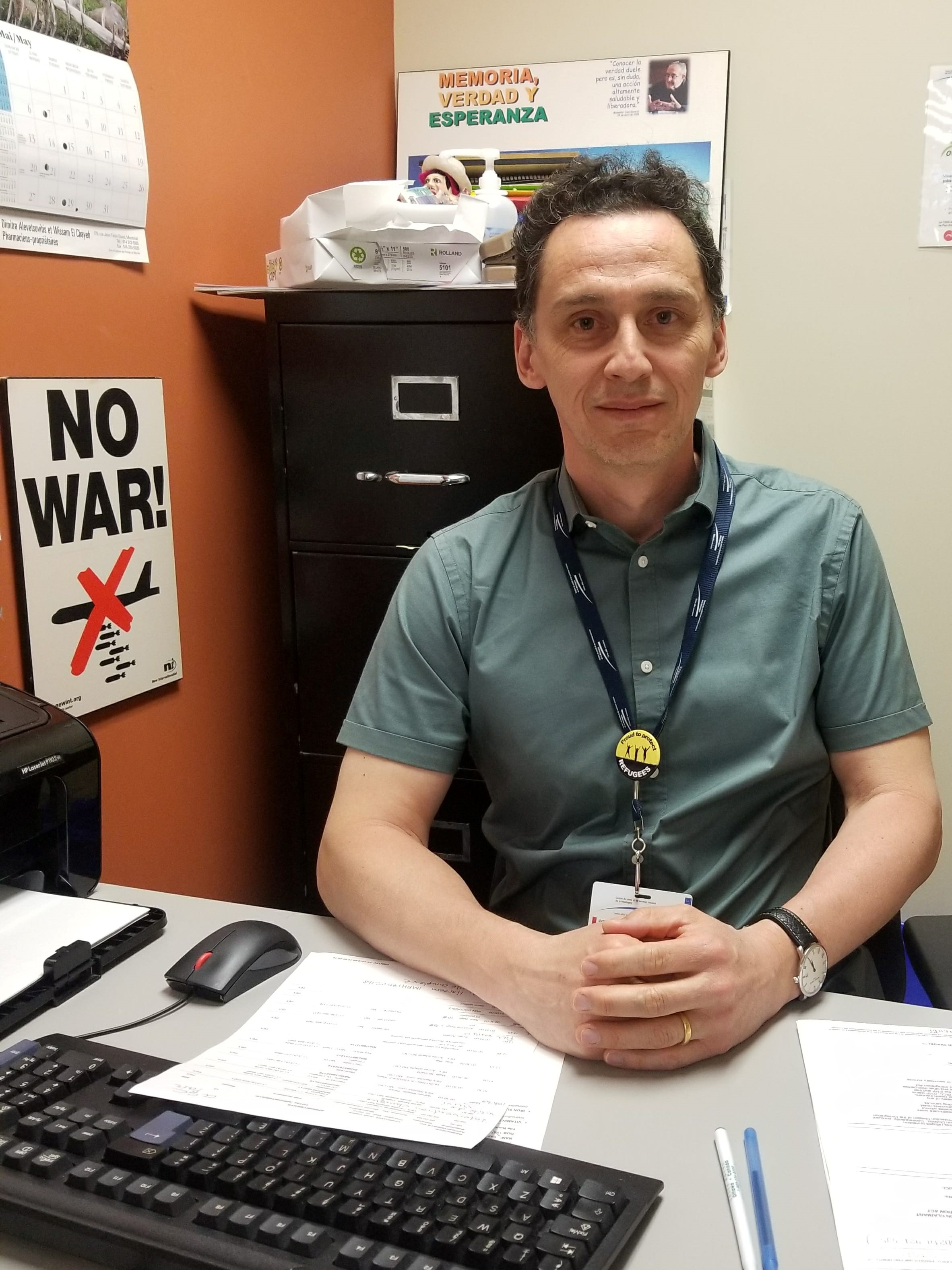

An interview with Juan Carlos Chirgwin

Dr. Juan Carlos Chirgwin is a family doctor working at CLSC Park Extension in Montreal. This health facility is located in a very multicultural area and serves a big population of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers. He also volunteers with Doctors of the World which is an organization that offers and promotes access to health care for excluded and vulnerable people.

Selon vous, quels sont les problèmes de santé les plus communs auprès des migrants et des réfugiés?

En général, les migrants et les réfugiés ont les mêmes problèmes de santé aigus et chroniques que le reste de la population. Il y a bien évidemment certaines conditions qui sont plus présentes dans leurs pays d'origines comme la tuberculose latente, l’hépatite chronique ou bien l’anémie ferritine auprès des femmes et des enfants. Cependant, ces dernières représentent une petite portion des maladies qui affectent quotidiennement les réfugiés et les migrants. Les maladies chroniques comme le diabète et la haute pression sont très communes auprès de ces populations et comme l’accès à un médecin de famille ou une infirmière dans leurs pays d’origine n’est pas toujours assuré, ils restent non diagnostiqués pour une longue période de temps et ils subissent silencieusement les différents dommages de ces maladies C’est seulement une fois au Canada qu’ils vont être vus par un médecin qui va les informer de toutes ces conditions et commencer les traitements. Malheureusement, dans la plupart des cas, des dommages sévères et permanents ont déjà été causés.

Est-ce que vous constatez une différence en termes d’observance thérapeutique (adhérence au traitement) entre la population générale et les migrants/réfugiés?

Oui il y a une différence! Mais cette différence n’est pas une question d’intelligence, mais bien une question d’éducation. Dans plusieurs pays à travers le monde, l’accès à l’éducation est encore limité et restreint. Il arrive donc que des patients n’aient pas terminé le secondaire ou même le primaire dans leur pays d’origine. Alors, il est vraiment difficile pour ces personnes de comprendre l’importance et le fonctionnent des traitements. Par exemple, si un patient est atteint du diabète de type II, il va recevoir une prescription de Metformin avec plusieurs renouvellements. Cependant, ce n’est pas tout le monde qui comprend que le diabète est une maladie chronique pour laquelle il faut prendre des traitements à vie. Il m’est donc déjà arrivé de voir des patients arrêter de prendre leurs pilules directement après avoir terminé la première boîte, car ils ne savaient pas qu’ils devaient aller à la pharmacie pour les renouveler et que le diabète ne se traite pas avec seulement 30 pilules. Il est donc nécessaire d’être conscient de cette différence, mais ne pas porter de jugement, car après tout, nous aussi lorsque nous étions au primaire ou bien au secondaire, nous ne comprenions pas grand-chose à ces maladies complexes. Un autre facteur important pour les maladies comme le diabète et l’hypertension est le fait que souvent les patients ne ressentent pas directement les dommages et se portent plutôt bien. Alors ils ne sont pas toujours convaincus de l’importance d’adhérer aux traitements et vont avoir tendance à arrêter. Donc en tant que médecin, il est essentiel de prendre le temps d’informer nos patients afin qu’ils comprennent davantage leurs maladies et leurs traitements.

Quels conseils aimeriez-vous donner aux étudiants en médecine concernant ce sujet?

Je crois qu’il est primordial pour les futures générations de médecin d’être ouverts d’esprit et d’essayer de comprendre les raisons qui poussent ces personnes à quitter leurs maisons, leurs familles et leurs terres. Une fois que l’on comprend les facteurs « push and pull » de l’immigration, on réalise l’ampleur de ce problème et ce qu’on peut faire pour limiter ces situations. Prenez par exemple les compagnies minières canadiennes en Afrique qui prennent le cuivre, l’or et le diamant de différents pays afin de commercialiser ces ressources. Cependant, cela crée une instabilité économique et sociale dans ces pays qui deviennent donc des zones dangereuses et forcent des individus à fuir. Même chose avec les industries d’armements qui vendent des armes et des véhicules à d’autres pays, menant à de la violence et des guerres. Lorsque ces personnes décident d’immigrer au Canada, avons-nous vraiment le droit de leur refuser l’entrée sachant que l’on a une responsabilité dans les problèmes qui les ont poussés à venir? Je pense donc qu’en comprenant cette dynamique, les étudiants en médecine seront plus aptes à traiter ces patients, mais aussi sauront utiliser leurs voix afin de défendre ces populations marginalisées.

Doctors of the World: https://www.medecinsdumonde.ca/en/

Push and Pull factors of Migration: http://www.bbc.co.uk/schools/gcsebitesize/geography/migration/migration_trends_rev2.shtml

-

Week 2: The Social Determinants of Refugee Healthcare

An interview with local expert, Dr. Meb Rashid

Dr. Meb Rashid is a Toronto-based family physician who specializes in refugee healthcare. He is a co-founding physician of Canadian Doctors for Healthcare, and the current Medical Director of Women's College Hospital's (WCH) Crossroads Clinic for refugees. This clinic provides comprehensive medical services to newly arrived refugee clients for their first two years in Toronto.

What are some of the barriers to getting adequate health care as a refugee or claimant?

It really depends on the refugee we are considering and how you define adequate healthcare. Many refugees and refugee claimants rely on using walk in clinics for their care. These serve a purpose but such intermittent care is not ideal for refugee populations.

There are some refugees who are immensely resourceful and are able to navigate the healthcare system and connect to appropriate care. Others face certain challenges inherent in navigating a complicated medical system. How can you find a doctor when in many areas there exists a shortage of healthcare providers and many have full practices? There are also more practical issues such as language discordance - those who don’t speak English or French - and lack of interpretation services. Access to interpreters is quite varied in the healthcare setting. Additionally, health insurance is a huge issue. Many refugees rely on the Interim Federal Health Plan, which is filled with nuances and not well known by physicians. It adds an extra layer of complexity when physicians are not familiar with what is covered for their patients.

One other issue which is often a struggle for us, is the lack of emphasis on primary care. Many refugees, particularly early in their migration process, have a number of competing priorities. They need to navigate housing, school for their children, how to navigate public transit etc.. It’s easy to de-emphasize health care particularly if one does not have any pronounced symptoms. Additionally, many people originate in parts of the world where one only visits a health care provider when they are sick. The idea of prevention is not always fundamental to people’s conception of health care. For all these reasons, connecting people to a primary care provider early in their migration trajectory can be a challenge.

You spoke about defining “adequate healthcare” for this population. What does that look like for you?

For us at the Crossroads Clinic, adequate healthcare means connecting our patients to primary care early in their migration trajectory. This is important for all refugees for several reasons. First, there is a tremendous amount of subclinical disease in refugee populations, including a significant prevalence of health care conditions such as hepatitis B but also chronic conditions such as hypertension and diabetes. Often these conditions are undiagnosed and thus there is a tremendous benefit to connecting people to primary care to allow for ensure that such conditions are recognized and addressed before complications arise.

More than anything, however, adequate healthcare is about developing a relationship with your patient and providing the support that people require. All refugees face unique challenges and may require different forms of medical assistance or connection to resources. Ensuring the creation of a safe and trusting environment where refugees can share their challenges and concerns is critical to providing care for refugee populations.

What are some of the immediate SDOH that refugees face as they navigate a new environment?

For most refugees, the social determinants play an immense role in their health. In particular, language acquisition is a tremendous challenge, but this obviously depends on the age they migrate. Children acquire language skills very quickly but this may create an imbalance of power in families where they end up being the source for accessing Canadian society for entire family.

Other challenges include finding housing and employment. Housing is increasingly inaccessible across the country. It can be difficult finding work in a profession that honors the skills that a newcomer had cultivated in their country of origin. For all these years, most refugees live in poverty for their first few years in Canada.

What are some of the long term health consequences of these barriers?

In Canada, there is still a paucity of literature that describes the health care trajectory of refugee populations. Although all refugees are fleeing persecution, they are immensely different. Some are highly educated urbanites; others may have had limited education access to education. Health outcomes and daily challenges vary.

There is some data showing that most refugees do very well over time. This is likely due to a selection bias: those that have managed to make it to Canada have often been able to overcome immense obstacles. They are the survivors and most have endured journeys that would have been very difficult for the frail and those that struggle with significant health issues. Refugees develop a tremendous resiliency and this serves them well over time in Canada.

Our experience at the Crossroads Clinic has demonstrated two factors that impact the long term health of refugee populations. First, where subclinical conditions are recognized and addressed, there is an opportunity to manage conditions before they cause significant health outcomes with the resulting challenges on successful settlement. The second is directly dependent on the social determinant of health. People tend to do better when they can find good jobs, when they are united with family, when they find housing in neighborhoods where they can thrive. Where these opportunities are available, refugees do very well.

What is the number one thing as a medical student that we should be aware of when dealing with this population?

The most important thing for us to consider in working with refugee populations is how to acquire people's trust. As medical professionals - students and physicians - we must ensure that we are sensitive to their unique struggles. Remember that for some, they may be detached and even reticent about connecting to care. This may be due to previous trauma including exposure to war or torture and sometimes even torture in a setting where health care workers were present. Thinking about ways to cultivate the relationship is a challenge but approaching patients with humility and kindness goes a long way to beginning that relationship.

Another thing for health care workers to consider is the importance of trying to support newcomers with the social determinants of health. Whether it is writing support letters or advocating for issues around housing, this not only aids refugees in addressing their issues, it also helps to develop the relationship and acquires the trust of our patients.

What are some resources to learn more?

If you’re interested in getting involved or learning more, you can reach out to refugee clinics across the country. There are clinics now in most urban areas across Canada including the Crossroads Clinic here in Toronto.

Some other national organizations to get more information include: Canadian Council for Refugees (http://ccrweb.ca), the College of Family Physicians of Canada (http://www.cfpc.ca/Refugee_Health_Care/), Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health (http://www.cfpc.ca/Refugee_Health_Care/). There also exists a national listerv for physicans that work with refugee populations and those students that are interested in joining can contact me directly at [email protected].

Links to clinics:

Bridge Refugee Clinic, Vancouver https://www.refugeehealth.ca/

Calgary http://mosaicpcn.ca/Programs/Pages/

Refugee-Health-Services.aspx

Saskatoon https://www.saskatooncommunityclinic.ca/reach-refugee-health-clinic/

Kitchener-Waterloo http://family-medicine.ca/clinics-services-programs-and-events/clinics-3/refugee-health-clinic/

Ottawa https://onhc.ca

Montreal https://www.medecinsdumonde.ca/fr/

QC http://www.jhsb.ca/fr/services-medicaux/clinique-sante-des-refugies

St John’s http://www.med.mun.ca/munmedgateway/About-Us.aspx

Halifax http://www.nshealth.ca/content/newcomer-health-clinic

-

Week 1: Access to Care

Access to Care

- What are the legal barriers that refugees and migrants face that directly or indirectly impact health?“A person’s immigration status in Canada can impact their physical and mental well-being in many ways. To begin, access to health insurance to cover health services is dependent on one’s immigration status. Canadian citizens and permanent residents are entitled to provincial health care. Refugee claimants, including failed refugee claimants, are entitled to Interim Federal Health, which provides them with access to basic health care services but is not as broad as provincial health insurance programs. People who have temporary status in Canada (visitors, students, workers with short term work permits) are not entitled to provincial health insurance and are expected to pay for their health care needs. Likewise, people without any status in Canada are not entitled to health government funded insurance coverage. Lack of and/or limited health insurance means that refugees and migrants will often access health services only when their health is in crisis.

A person’s lack of immigration status can also impact on their physical and mental health other ways. The length of time it can take to regularize one’s immigration status in Canada can take a toll on a person’s health as they worry and wait to obtain status. Unfortunately, the resulting deterioration of a refugee claimant’s physical and mental health can also affect their ability to obtain status. For example, refugee claimants whose mental health deteriorates as they wait for their hearing before the Immigration and Refugee Board may have a harder time testifying in the hearing room. This can have a negative impact on their credibility and potentially affect the outcome of their refugee claim.

Finally, separation from loved ones can also have an impact on a person’s mental and physical health. I have many clients who were determined to be Convention refugees in Canada and who, when they applied for permanent residence, included their dependence overseas. Because their loved ones are often in a precarious situation back home, the worry and anxiety my clients have while they wait to be reunited with their family members can have an impact on their physical and mental well-being.”

Laila Demirdache, Immigration and Refugee Lawyer

Education links

What are the different immigration classes in which people can be accepted into Canada?

Refugees make up a small number of the immigrants to Canada along with economic immigrants, family class and a small number of “other”What does it mean to be a refugee?

1951 Geneva Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees:- a person owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted

- for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion

- is outside the country of their nationality, and is unable to or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail him/herself of the protection of that country

Note: this definition does not include Internally Displaced Persons (IDP’s), those that have fled situations that may be very similar to refugees but have not crossed international borders.

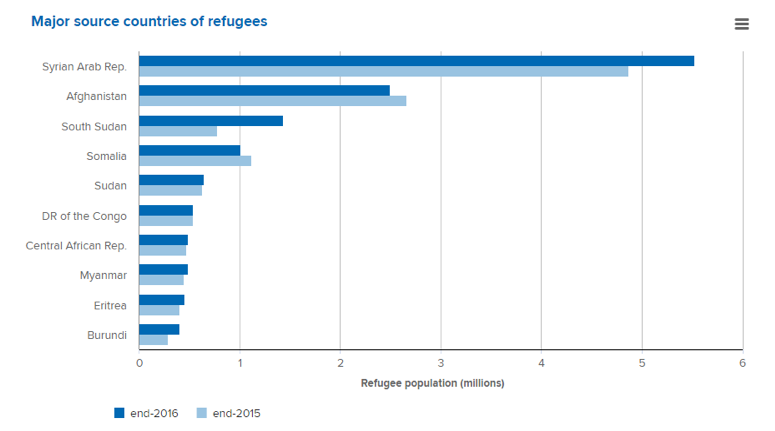

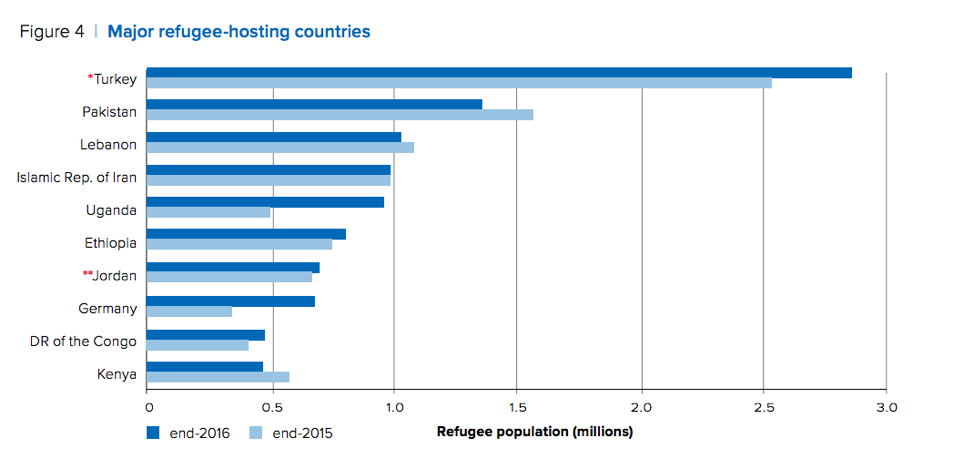

How many refugees are there globally? Where do they come from? Globally where do most refugees migrate?

In 2016, 65.6 million forcibly displaced:- 22.5 million refugees

- 40.3 million internally displaced people

- 2.8 million asylum seekers

- HIGHEST NUMBERS EVER RECORDED (UNHCR, Global Trends Forced Displacement in 2016)

Source: UNHCR, Global Trends Forced Displacement in 2016

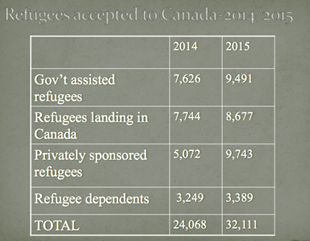

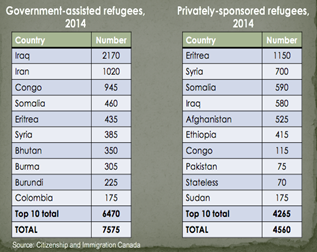

How many refugees migrate to Canada each year?

How many refugees migrate to Canada each year?

Health insurance

- Three month wait for OHIP in Ontario (does not apply to refugees)

- Visa student, foreign worker program-private insurance (some exceptions)

- Refugee claimants-Interim Federal Health Program

- Privately Sponsored and Government Assisted Refugees-OHIP and IFH

Federal health Program

- Provides access to physicians, diagnostics, laboratory testing (as with provincial health programs)

- Also provides medication access as well as emergency dental and vision care (identical to Social Assistance Programs)

- Provided to all refugees

- For urgent and essential care but has been interpreted very broadly

- In 2012, All refugees lost access to federal coverage for “supplemental services”- medications, emergency dental services, optometry services, access to assisted devices and prosthetics (Gov’t Assisted Refugees taken off the list June 30, 2012)

- Some lost access to essentially all medical care

Below is a video link for a brief introduction regarding Canada’s refugee protection determination system and information for refugee claimants, counsels and stakeholders.

- Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada. (2017, Sept 26). An Introduction to Canada’s Refugee Determination System [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gG52QiQr574

Below is a link with a list of 10 community agencies that you can contact to access high quality interpreters which is funded under the Ministry of Citizenship. Translators services are available in up to 50 differents languages in almost all cities centers across Ontario.

For more information, please visit:

https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/refugees/canada-role.html

https://www.loc.gov/law/help/refugee-law/canada.php

http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/asylum-seekers-support-housing-1.4252114

https://www.canadavisa.com/canadian-immigration-refugee-status.html

http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/helpcentre/answer.asp?qnum=098&top=11

- What are the legal barriers that refugees and migrants face that directly or indirectly impact health?“A person’s immigration status in Canada can impact their physical and mental well-being in many ways. To begin, access to health insurance to cover health services is dependent on one’s immigration status. Canadian citizens and permanent residents are entitled to provincial health care. Refugee claimants, including failed refugee claimants, are entitled to Interim Federal Health, which provides them with access to basic health care services but is not as broad as provincial health insurance programs. People who have temporary status in Canada (visitors, students, workers with short term work permits) are not entitled to provincial health insurance and are expected to pay for their health care needs. Likewise, people without any status in Canada are not entitled to health government funded insurance coverage. Lack of and/or limited health insurance means that refugees and migrants will often access health services only when their health is in crisis.